Posted by J. A. Mills on March 25th, 2020 in China, News, Tigers

What happened after the book ended? Did China finally bend to international will and stop farming tigers, rhinos, and bears like cows and pigs? Readers still write to ask me five years after Beacon Press published Blood of the Tiger: A Story of Conspiracy, Greed, and the Battle to Save a Magnificent Species. My answer, as of this moment—when COVID-19 has shut down much of the world—is this: You can watch the rest of the story unfold in real time.

As I write, President Donald Trump has blamed China for not stopping the spread of COVID-19, renaming it the “China virus” and provoking racist assaults on Asian Americans. Chinese authorities have suggested that a member of the US military brought the virus to the disease’s epicenter in the city of Wuhan. Politicians and conservation organizations are pointing the finger at teeming “wet markets” across Asia, where all manner of wildlife is dragged from forests and kept in squalid conditions before being butchered by sundry inhumane and unsanitary means. If there ever were a petri dish for spawning emerging diseases, these markets fit the bill.

Scientists have concluded that COVID-19 was not manmade in a laboratory. Rather, the virus somehow jumped from animals to humans, who spread it worldwide. Much like the scenario in the 2012 Hollywood movie Contagion, which many homebound people are watching in astonishment and horror these days.

Researchers surmise that the 2003 SARS coronavirus may have originated from bats infecting civets, a favorite bush meat cuisine in China. They’ve pinned the 2012 MERS coronavirus on camels, perhaps in the Middle East. Scientists haven’t pinpointed the exact origin of the Ebola virus, but they suspect bats and non-human primates in the Democratic Republic of Congo–yet another zoonotic transfer of disease from animals to humans. Scientists speculate the 1918 flu pandemic that killed some 50 million people worldwide jumped from birds to humans, perhaps originating in the United States. Seasonal flu viruses generally come from somewhere in Asia, sometimes linked to livestock.

“Historical data show that all pandemic influenza occurrences originated from animals,” according to the World Health Organization. The nonprofit organization Freeland recently launched a campaign urging people to “write to your government and ask them to ‘protect people and wildlife by banning wildlife trade as a matter of public health and environmental security in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.’”

In truth, no one can identify, beyond the shadow of a doubt, the genesis of COVID-19 at this time, although Chinese scientists confirmed it is a close relative of SARS. Nonetheless, faulting China has become a global meme. Chinese authorities, if only for the sake of the country’s self-preservation, have acted accordingly.

“The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, or China’s top legislature, during a session Monday adopted a decision on thoroughly banning the illegal trading of wildlife and eliminating the consumption of wild animals to safeguard people’s lives and health . . . including those that are bred or reared in captivity . . . ,” China’s official Xinhua news agency reported on February 24.

“There has been a growing concern among people over the consumption of wild animals and the hidden dangers it brings to public health security since the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak,” Zang Tiewei, spokesperson for the Commission of Legislative Affairs of the National People’s Congress, said after the ban was approved.

Sounds promising for tigers, rhinos, bears, and other endangered wild animals now commercially farmed in China. But here’s the rub, as spelled out by Xinhua: “The decision also stipulates that the use of wild animals for non-edible purposes, including scientific research, medical use and display, shall be subject to strict examination, approval and quarantine inspection procedures in accordance with relevant regulations.” Tigers are farmed for their bones, rhinos for their horns, and bears for the bile in their gall bladders, all for use in traditional Chinese medicine. So, while wet markets in China may be closing, factory farms for endangered species appear to be carrying on as usual, despite the inherent disease risk.

Sounds promising for tigers, rhinos, bears, and other endangered wild animals now commercially farmed in China. But here’s the rub, as spelled out by Xinhua: “The decision also stipulates that the use of wild animals for non-edible purposes, including scientific research, medical use and display, shall be subject to strict examination, approval and quarantine inspection procedures in accordance with relevant regulations.” Tigers are farmed for their bones, rhinos for their horns, and bears for the bile in their gall bladders, all for use in traditional Chinese medicine. So, while wet markets in China may be closing, factory farms for endangered species appear to be carrying on as usual, despite the inherent disease risk.

Here’s the potentially good news, as I see it. This is the moment—perhaps the last, best moment—for the world to finally put an end to commercial wildlife farming promoted by China and growing across Southeast Asia, South Africa, and elsewhere. Farming that has raised demand for wildlife parts and products and put a price on the head of every tiger, rhino, and bear in the wild, because many consumers believe those taken from the wild are of superior quality—not unlike wild versus farmed salmon.

While China may or may not be the origin of the current pandemic, its people were hit hard by both SARS and COVID-19. “The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed the issue of wildlife trade into the global spotlight as a threat to our public health, global economy and security,” wrote Grace Ge Gabriel, regional director for Asia at the International Fund for Animal Welfare. “I am encouraged to see China step up to curtail wildlife trade. Breaking the petri dish that grows epidemics needs global coordination and vigorous enforcement along every link in the trade chain.”

Still, powerful political and economic interests, inside and outside the Chinese government, will push back on China’s new ban as soon as the immediate dangers of COVID-19 have passed, just as they did after similar moments of inflection detailed in Blood of the Tiger. They may already be doing so. The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) just reported that China’s National Health Commission is recommending a traditional medicine treatment for COVID-19 that contains bear bile. This brings to mind the insistence by Chinese wildlife authorities that tiger bone was essential for treating SARS.

“Restricting the eating of wildlife while promoting medicines containing wildlife parts exemplifies the mixed messages being sent by Chinese authorities on wildlife trade,” EIA China specialist Aron White said in a statement posted Monday.

Chinese wildlife authorities charged with regulating—and promoting—China’s wildlife farms balked at President Xi Jinping’s 2015 deal with President Barack Obama to end ivory trade. But Xi prevailed. I joined my fellow conservationists in hoping that Xi and Obama’s successor would broker similar agreements on ending all commercial trade in parts and products from tigers, rhinos, bears, and other endangered species coveted in Chinese medicines and prestige cuisine. Trump’s election dashed those hopes.

Now we have COVID-19, which has brought China’s commercial wildlife trade to the attention of billions of people around the world who are currently living in fear for their lives and livelihoods. If the world continues to blame China—rightly or wrongly—for spawning this health and economic crisis that spans the planet, Xi will have to demonstrate containment of his country’s breeding grounds for future pandemics. Permanently shuttering wet markets, bush meat restaurants, and massive wildlife farms would be one highly credible, verifiable way for China to regain the trust and good graces of the world.

Posted by J. A. Mills on June 21st, 2016 in China, Farming, Geopolitics, U.S.

Call it superpower leadership, sibling rivalry, or rising to the occasion. Whatever the label, the presidents of China and the United States have joined forces to literally save the world.

This is how the world achieved game-change on climate change: U.S. President Barack Obama and China’s President Xi Jinping spoke one-on-one about concerns over human-caused greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions speed-warming the planet. The U.S. acknowledged that it, too, has a problem with GHG emissions. Then the world’s number one and number two GHG emitters—China and the U.S. respectively—jointly pledged to limit their climate impacts and lead the world to do the same.

Something similar is happening with ivory. Britain’s Prince William raised concerns about China’s ivory consumption in a private meeting with President Xi Jinping. The U.S. acknowledged that it, too, has an ivory trade problem. The U.S. burned six tons of ivory stockpiles in a gesture of good faith, after which China burned 6.1 tons. Then China and the U.S.—the world’s number one and number two largest consumers of wildlife—made a joint pledgeto stop ivory trafficking at home and abroad, and to ban legal domestic ivory trade. The U.S. announced a “near-total” ban on ivory trade the week before this month’s China-U.S. Strategic and Economic Dialogue, after which China announced it would set a timetable by the end of the year for phasing out commercial trade in ivory.

Through these bold, unprecedented measures, Presidents Xi and Obama may save humanity from climatic catastrophe and elephants from extinction. Will they go a step further and help the other wild species—such as tigers and rhinos—that are being hunted down for their commercially valuable parts?

When I went to China for the first time in 1991 to investigate bear farming, I learned the country intended to farm bears and a long list of other rare and threatened species “just like cows and pigs,” as my main government escort phrased it. In fact, China’s Wildlife Protection Law mandated the farming of this long list of wildlife for commercial trade and consumption. What most people do not know is that China now battery farms tigers and has recently begun farming rhinos, all under blessing of the country’s Wildlife Protection Law.

This law is up for revision now, and Chinese legislators, business leaders, conservationists, animal welfare advocates, and celebrities have pushed for the farming and consumption mandates to be removed. Unfortunately, China’s State Forestry Administration—the agency charged with protecting species in the wild—helped start, build and promote bear, tiger, and rhino farms. This is the same agency that advocated for so-called “limited” legal international trade in ivory on behalf of China’s ivory traders, which resulted in the recent wholesale slaughter of African elephants, undermining the 1989 international trade ban that has allowed them to make a dramatic comeback in the wild.

Surveys have repeatedly shown that majorities of Chinese people support bans on trade in ivory, tiger bone, and rhino horn. However, the results of a new study by Chinese researchers also found that consumers in China continue to prefer wild-sourced products over farmed-raised because they believe those from the wild are more effective. In other words, if trade in these commodities becomes legal again, buyers will prefer those taken from the wild.

“For many species, commercial breeding and legalized trade in farmed products will have the opposite effect to what is desired for conservation,” according to another new study. “[The] main reasons are consumers’ preference for wild products…and laundering of illegal products into the legal wildlife trade.”

Researchers from Princeton University and the University of California at Berkeley just releasedresults from their analysis of the repercussions of “limited” legal ivory trade from Africa to China and Japan in 2008. “The intuition that legalization will reduce illegal production is not always true,” said co-author Nitin Sekar, who began the study as a graduate student at Princeton and received his doctorate in 2014. “The economic intuition was that if we allow the sale of some legal ivory in Japan and China, then there would be fewer people left to purchase it illegally. We found that that intuition was incorrect. The black market for ivory responded to the announcement of a legal sale as an opportunity to smuggle even more ivory.” Said Sekar’s co-author Solomon Hsiang, now an associate professor of public policy at UC Berkeley: “I used to be a strong believer in legalization as a crime-reducing policy, but this has really forced me to rethink that. [W]hen people talk about legalization, it may be smart in some cases, but in which cases is not as obvious. This is a case study for how wrong it can go.”

So, why is China’s State Forestry Administration in the business of promoting rather than stopping trade—legal and illegal—in parts and products from endangered species when that approach went so dramatically wrong with elephant ivory? It all goes back to China’s Wildlife Protection Law. When the law debuted the 1980s, it not only mandated the farming and consumption of wildlife, but deemed the endeavor virtuous and of great benefit to the People’s Republic of China. This mandate grew from Mao Zedong’s emphasis on animal husbandry as a cornerstone to the success of Communist China. Mao’s regime even ordered the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to help ensure the success of animal husbandry and also medicine manufacturing. Scholars have noted that China’s decision to join CITES—the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora—in 1981 went against the priorities of the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, the Ministry of Public Health, and the PLA. In fact, the PLA was “implicated in protecting the smugglers of tiger bone and rhino horn” after China banned their importation to comply with CITES.

The PLA, several government ministries, pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as provincial and municipal governments invested money and manpower in establishing China’s bear and tiger farming industries, the country’s new rhino horn farming effort, and unsuccessful attempts to farm musk deer and pangolins. Another key player was China’s Northeast Forestry University, which, until recently, produced all of the country’s biologists—some of whom hold key leadership positions in today’s State Forestry Administration. This is why the only way to stop this growing drive for commodification of bears, tigers, rhinos, and dozens of other wild species is to take the matter out of the hands of those married to these mandates from the past, which, like the unmitigated burning of fossil fuels, are proving dangerous to Earth as the global community knows and loves it.

Nothing short of Xi Jinping and Barack Obama forging a bilateral agreement like their climate and ivory agreements will stop the enduring and expanding effort to commodify a long list of the world’s most beloved wild species. As the joint China-U.S. climate statement of November 2014 says: “The seriousness of the challenge calls upon the two sides to work constructively together for the common good.”

Posted by J. A. Mills on November 24th, 2015 in China, Farming

“China farms tigers? Why didn’t I know that?” This is the most common comment I hear when I talk about China’s industrial tiger farms and my book Blood of the Tiger, which was rereleased today in paperback.

“Yes,” I reply, “they farm them ‘just like cows and pigs.’ That’s how a Chinese government official described it to me during my first visit to China back in 1991.”

In 2015, China farms tigers by the thousands to make luxury products such as tiger-bone wine, even though China’s State Council banned trade in tiger bone in 1993. Even though CITES—the U.N. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species—decided in 2007 that tigers should not be farmed for their parts and products. Even though the mainstream traditional Chinese medicine industry no longer wants or needs tiger bone. Even though polls repeatedly show that the Chinese public supports the 1993 ban.

Tiger farming is a business venture, plain and simple. It is about wealth, not health. If China’s government lifts its 1993 ban—which there is intense industry pressure to do—a handful of investors stand to become very rich from the tiger skeletons now steeping in vats of wine inside farm wineries.

Here’s what befuddles me most: Why is the “fox” in charge of the tiger “hen house” at CITES? Why did a United Nations treaty put China’s State Forestry Administration (SFA)—the very agency that promotes tiger farming and helped build some of those wineries—in charge of the Asian Big Cat Working Group, which is charged with assessing what’s going on with the world’s captive tigers?

The SFA reported in 2013 that there were “more than 5,000” tigers, primarily on two tiger farms—nearly twice the number now in the wild. The SFA has for years openly advocated legal trade in tiger bones from farms as a “conservation” tool and has admitted to already allowing trade in skins from farmed tigers.

Here’s the fatal flaw in the proposed “limited” legal trade scenario for tiger farms: Reopening tiger bone trade in China will rekindle a demand that nearly died out after the 1993 ban. The mere existence of tiger farms and their burgeoning populations has stimulated demand. If legal trade in farmed tiger-bone products is allowed, some portion of China’s 1.4 billion potential consumers will want the “Champagne” version—the bones of wild tigers, which consumers consider superior, more prestigious and exponentially more valuable. Even if only a tiny fraction wants bones from the wild, the result would be a relative tsunami of demand.

Poachers in Africa have killed many more than 100,000 elephants since China first allowed “limited” legal trade in ivory back in 2008. How long would Asia’s mere 3,000 wild tigers last faced with unleashed demand from China?

So, why is it that China’s tiger-farming champions are in charge of a U.N. treaty’s effort to ascertain what’s going on with captive tigers and what threat they pose to wild tigers?

In answer to a CITES questionnaire about captive tigers sent out by the SFA on behalf of the Asian Big Cat Working Group, the SFA sent back a response that gave no numbers and provided answers that obfuscated more than enlightened about the legal status of trade in products from China’s tiger farms. Shouldn’t that be enough to disqualify the SFA from leading the working group?

I have been around CITES long enough to know that member countries must know that China’s SFA has an overriding conflict of interest with potentially epic consequences in leading the Asian Big Cat Working Group. I also know that many CITES member countries are now beholden to China or afraid of China or otherwise reluctant to question anything China does. But the SFA is not China. And the SFA isn’t even close to being an objective arbiter of matters affecting the fate of wild tigers.

CITES parties—including the United States—and the CITES Secretariat should quietly and politely relieve the “fox” from its charge over the U.N. tiger “hen house.”

Posted by J. A. Mills on March 30th, 2015 in China, Farming, Rhinos, Tigers

Surely China’s President Xi Jinping would not support the commodification of tigers and rhinos if he knew all the facts.

What stands in the way of his enlightenment is the State Forestry Administration (SFA), which is his staff’s go-to ministry on the issue. And the SFA has a conflict of interest. It’s giving its all to enforcing China’s 1980s-vintage Wildlife Protection Law, which literally calls for the “domestication” and “utilization” of a long list of endangered species so China will have strategic reserves of them and their parts and products. But here’s the pivotal thing: Significant factors have changed since that law came into effect in 1986. Most importantly, the mainstream traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) industry does not need or want tiger bone and rhino horn anymore. The industry decided years ago that it wanted to go global, which was not going to happen in a big way if its practitioners continued to consume rare wild species the world adores. It was a solid strategic business decision.

So now China has, on the one hand, 6,000 tigers in SFA-supported battery farms with wineries brewing a fortune in tiger-bone wines. It also is trying to buy up South Africa’s rhino horn stocks, while simultaneously starting to farm more with founder stock of 121 rhinos sent to China by South Africa. None of this would make sense unless the SFA intends to see China’s 1993 ban on trade in tiger bone and rhino horn lifted.

So now China has, on the one hand, 6,000 tigers in SFA-supported battery farms with wineries brewing a fortune in tiger-bone wines. It also is trying to buy up South Africa’s rhino horn stocks, while simultaneously starting to farm more with founder stock of 121 rhinos sent to China by South Africa. None of this would make sense unless the SFA intends to see China’s 1993 ban on trade in tiger bone and rhino horn lifted.

On the other hand, Chinese news media recently reported that 35 delegates of the National People’s Congress are calling for revision of the Wildlife Protection Law within this year. Delegate Luo Liansheng, vice president of Nanchang Aviation University, said he would like the endangered-species utilization mandate removed from the law. He told the press that farming threatens wild populations because it stimulates demand for their more-coveted parts. (Think of bones from farmed tigers as cubic zirconia and bones from wild tigers as flawless diamonds.) Luo went as far as suggesting a ban on farming endangered species. Delegate Jiang Jian, director of Qufo Hospital, told the Legal Daily that the law’s intended purpose of protecting species in the wild is weakened by its simultaneous call for consumption of the very same species. Delegate Zheng Xiaochang, chairman of Anhui Tianfang Tea Group, pointed out that current system of wildlife farming can provide cover for illegal trade.

Has President Xi Jinping heard these voices? Does he know the mainstream TCM industry has disavowed use of tiger bone and rhino horn? Has he seen results of the polls that repeatedly show majorities of his people want the ban on trade in tiger bone and rhino horn to stay in place—that they say trade in such items brings shame to their beloved country? Does he know the Chinese public is not crying out for tiger bones or rhino horns? Does he realize that only an elite group of wealthy consumers wants to buy them and another elite group wants to get wealthy selling them? The survival of these species in the wild may depend on President Xi knowing these facts.

The SFA is not the monolithic Chinese government any more than the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service embodies the U.S. government. But we will not know if Xi Jinping knows the whole truth about the commodification of tigers and rhinos until governments of the world insist this metamorphosis of our planet’s rarest species into commodities be taken above the SFA’s head. Unfortunately, because of the SFA’s bullying government officials and NGOs into silence on the matter, that may only happen if large numbers of the public pressure their elected government representatives to do so.

Posted by J. A. Mills on March 11th, 2015 in China, Farming, News, Tigers

I’ve been asked whether China’s decision to open an office dedicated to the protection of wild tigers marks significant progress. The short answer is, “Yes and no.”

This announcement is significant news in that it tells people in China that wild tigers are important. The fact that President Xi Jinping recently asked about the needs and habits of wild tigers is even more encouraging.

News of this new office is less significant when viewed in a fuller context. China’s State Forestry Administration (SFA) has for many years talked about its support for saving wild tigers and stopping illegal tiger trade. What SFA officials did not say—and still do not say—is that they were and are investing significantly more effort and money in growing China’s tiger farming industry, upping its capacity to brew tiger-bone wine and seeking international approval for reopening legal trade in luxury products made from farmed tigers. The SFA’s Wan Ziming wrote in a 2009 magazine article that China would be prepared to appeal all the way to the International Court of Justice in The Hague should the UN treaty on international trade in endangered species—CITES—not give its blessing.

Forgive me for repeating myself: the problem with tiger farming is that it stimulates demand for tiger products, which, in turn, stimulates poaching of wild tigers because consumers consider products from wild tigers superior in quality, far more prestigious and exponentially more valuable. Some investors are even buying products made from wild tigers as they would rare art or gold.

Forgive me for repeating myself: the problem with tiger farming is that it stimulates demand for tiger products, which, in turn, stimulates poaching of wild tigers because consumers consider products from wild tigers superior in quality, far more prestigious and exponentially more valuable. Some investors are even buying products made from wild tigers as they would rare art or gold.

As long as China allows some 6,000 tigers on farms with tiger-bone wine brewing in their wineries, it will continue to stimulate demand for and poaching of wild tigers. The commercial force of that demand will trump any benefits that could possibly come from a single government office with a mandate to protect wild tigers. In fact, some observers might find it a bit cynical for China to open such an office while it continues to farm tigers at an industrial scale.

The SFA appears to support a new World Wildlife Fund (WWF) campaign toward “zero poaching” of wild tigers. “It’s great they are working towards zero poaching,” says Debbie Banks, head of the Environmental Investigation Agency’s tiger program, “but China, and the countries that are following their tiger-farming business model, must also work towards zero demand for tigers.”

Debbie’s point is the bottom line. Until China does all it can to protect wild tigers and, more importantly, to stop consumer demand for tiger parts and products from all sources, little if anything will improve for wild tigers. As the WildAid slogan so aptly says, “When the buying stops, the killing can too.” And only then.

Posted by J. A. Mills on March 4th, 2015 in China, News, Tigers

So far in 2015, the world has seen two rounds of effusive headlines about tigers “roaring back” in the wild—first from India, then from China. Unfortunately, wild tigers are nowhere near “roaring back” anywhere. In fact, their numbers are down by half what they were 20 years ago, while threats to their survival continue to escalate.

Sure, everyone prefers good news. And conservation groups must show donors that some sort of success has been bought with their dollars. But hyperbole can lead to the widespread false impression that wild tigers are much better off than they are.

“India’s tigers come roaring back,” World Wildlife Fund (WWF) announced on January 20. “India’s tiger population has significantly increased, according to the 2014-15 India tiger estimation report released today. Recent years have seen a dramatic rise in numbers….” The headline was parroted by news media around the world. But few, if any, that ran the story mentioned the fact that India’s tiger censuses are notoriously unreliable and sometimes dangerously wrong. In fact, just a month after the breaking good news, Indian and Oxford University scientists called India’s census techniques into question. “India’s tiger success story may be based on inaccurate census,” cautioned a headline in the UK’s Guardian. “Reports that India’s tiger population has risen by a third in four years are based on an unreliable count method,” said the subhead.

The second round of exaggerated good news came just as the Oxford report was throwing cold water on the first round. “This rare WWF video proves China’s tiger population is roaring back,” declared the Irish Examiner of camera-trap footage from 2014 showing an Amur tigress with two playful cubs about 20 miles from Northeast China’s border with Russia. “Many years of conservation work have led to this stunning footage—establishing conservation areas, building a population of prey animals and installing over one hundred infrared cameras in largely inaccessible areas,” said Shi Quanhua of WWF China.

What the story did not say is that wild tigers are all but extinct in China. The South China tiger is gone. There are an estimated 10 to 20 Amur tigers in Northeast China’s border region, and Indochinese tigers have been known to wander into Southwest China from Vietnam, although some experts say Vietnam’s wild tigers are now extinct. The fact that one tiger family is alive and well in Northeast China is indeed extraordinary, but it does not in any way constitute a “comeback” for wild tigers in China. Rather, it underscores the fact that the whole of China may have only one breeding tigress. Dale Miquelle, director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Russia Program, got it right when he told National Geographic: “Numbers may be slightly increasing in China, and the evidence of reproducing females is encouraging, but it is still a tiny population of, at most, a dozen or so. There is a long way to go before we can say that there is a viable population living in China.”

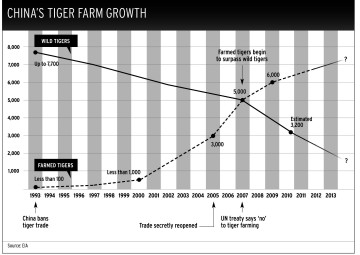

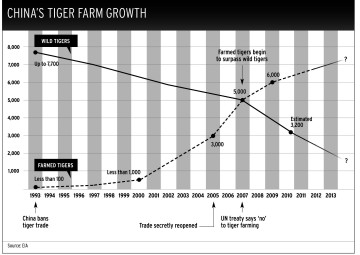

This graphic from Blood of the Tiger offers a quick overview of wild tiger numbers over that past 20 years. As the number of tigers in China’s farms went up, those in the wild went down. The correlation: demand increased for wild tiger parts and products as the burgeoning farms tacitly promised a reopening of tiger trade between the lines—which is where most mainland Chinese ascertain news from their government.

This graphic from Blood of the Tiger offers a quick overview of wild tiger numbers over that past 20 years. As the number of tigers in China’s farms went up, those in the wild went down. The correlation: demand increased for wild tiger parts and products as the burgeoning farms tacitly promised a reopening of tiger trade between the lines—which is where most mainland Chinese ascertain news from their government.

Just because wild tigers are not being slaughtered for their bones and skins at the same rate that elephants and rhinos are being slaughtered for their ivory and horns, respectively, no one should not assume that tigers are any less threatened by the organized criminal syndicates supplying wealthy Asian elites investing in luxury products that will become priceless with extinction. In fact, estimates say there are far fewer wild tigers (3,200) than elephants (500,000) or rhinos (29,000), and tigers are more disbursed in dense forest and grassland, making them far more difficult to find and poach than elephants or rhinos.

In future, it would be better for wild tigers if conservation groups and the media who cover them would curb their enthusiasm when the rare bit of good news arises. Headline bait may attract donors and readers but it only diminishes the chance that wild tigers will attract the amount of time, money and effort required to save them from the deadly threats that grow larger by the day.

Posted by J. A. Mills on February 18th, 2015 in China, Farming, News, Tigers, U.S.

The United States is one step from bringing trade sanctions against China for its domestic trade in tiger bone and rhino horn.

The fact is the US has been one step away since 1993, thanks to a legal petition filed by World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) with the Clinton administration. They did so under the Pelly Amendment of the Fisherman’s Protection Act, which gives the US mandate to punish countries whose nationals undermine international protections for endangered species. Not long after China’s State Council banned domestic trade in tiger bone and rhino horn in 1993, President Clinton put the sanctions on hold, where they remain today.

In July 2014, the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) asked the Obama administration to revisit them, providing lengthy documentation to show that China continues to ignore international agreements aimed at stopping tiger trade and allows legal trade in tiger products from tiger farms. The US Department of Interior confirmed it is reviewing EIA’s request.

Here’s the puzzling part. When WWF and NWF filed their petition back in the 1990s, the press releases went flying. Then-Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt publicly declared, “The Pelly Amendment requires us to address this destructive trade, and we have done so.” Now, in 2015, with wild tiger populations down by half and armies unable to stop the slaughter of rhinos for their horns, the same players are pretty much mum on the matter. At the same time, they and others have piled on in support of President Obama’s executive order to stop wildlife trafficking.

“Wildlife trafficking is pushing some of the world’s most iconic species toward extinction while driving a lucrative criminal industry and funding armed groups that fuel instability in countries around the globe,” said a White House blog on February 11. “In the last year, the United States invested more than $60 million in international programs to address this issue, including the provision of technical assistance and capacity-building activities to strengthen law enforcement and criminal justice systems, and reduce demand for trafficked wildlife.”

More than $60 million spent but not a peep about China battery farming tigers to make tiger-bone wine, which stimulates poaching of wild tigers because the bones of wild tigers are considered more potent and prestigious and are increasingly valued as investment assets. Also nothing about China’s nascent rhino farms and their role in quietly promising rhino horn to 1.4 billion potential consumers while the slaughter of rhinos for their horns continues to spiral out of control in Africa and Asia.

“In the early 1990s, we feared that Chinese demand for tiger parts would drive the tiger to extinction by the new millennium. The tiger survives today thanks in large part to China’s prompt, strict and committed action and US support for it,” said WWF’s Sybille Klenzendorf in 2007. “To overturn the ban and allow any trade in captive-bred tiger products would waste all the efforts invested in saving wild tigers. It would be a catastrophe for tiger conservation.” Exactly!

Indeed, the world owes a debt of gratitude to the governments of China and the United States—and WWF and NWF—for the fact we still have some 3,000 tigers remaining in the wild. Without their bold actions in the 1990s, how many would be left? Many fewer. Perhaps none.

Now a spectacular opportunity sits before us. The Department of the Interior’s revisitation of the active Pelly complaint against China for its tiger and rhino trade and the implementation of President Obama’s executive order on wildlife trafficking come just as China’s President Xi Jinping is preparing for his first state visit to the United States in September. What a timely opportunity for the US and China—with support from like-minded NGOs in the US and China—to forge a bilateral commitment to stop all trade in tiger and rhino products from all sources!

The good news is that you can encourage such game-changing action with just a few minutes of your time by contacting the White House and the Department of Interior. Your voice will matter, but only if your use it.

Posted by J. A. Mills on February 5th, 2015 in China, Farming, Geopolitics, News, Tigers

Authorities in China seldom respond to the consistent flow of new evidence that Chinese demand for tiger products drives poaching of wild tigers. When they do, it’s important to notice what isn’t said.

The New York Times recently wrote a courageous editorial about China’s “plunder” of Myanmar’s natural resources. “China’s insatiable demand for tiger and leopard parts, bear bile and pangolins has helped to transform the town of Mong La, near the Chinese border, into a seedy center of animal trafficking, prostitution and gambling,” it said. “The people of Myanmar… want this plunder stopped.”

The New York Times recently wrote a courageous editorial about China’s “plunder” of Myanmar’s natural resources. “China’s insatiable demand for tiger and leopard parts, bear bile and pangolins has helped to transform the town of Mong La, near the Chinese border, into a seedy center of animal trafficking, prostitution and gambling,” it said. “The people of Myanmar… want this plunder stopped.”

A few days later, China’s official Xinhua News Agency published a retort from Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hua Chunying. “We firmly disagree with the editorial,” Hua was quoted as saying. “We are committed to strengthening cooperation with our neighbors, including Myanmar, to tackle illegal activities, protect natural environment and safeguard the stability of border areas.”

No confirmation; no denial.

This week, Reuters published a story about an international anti-poaching conference in Nepal. “There is a culture among more and more wealthy people in China (to own tiger parts),” it quoted Michael Baltzer, leader of World Wildlife Fund’s Tigers Alive Initiative, as saying. “Tiger farming in China encourages (poaching) by stimulating demand for tiger parts,” said Debbie Banks, head of the Environmental Investigation Agency’s tiger program.

Two days later, the matter was raised at a press conference of China’s Foreign Ministry. “Some experts say that the soaring demand for tiger parts in China has caused a sharp decline in the tiger population, and frustrated efforts by all parties to protect wild tigers. How does China respond to this?” someone asked. “The Chinese government attaches great importance to protecting wild tigers and keeps improving laws and regulations protecting wild tigers,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei replied. “Poaching, trading of tiger bones and using them as medicine are fully banned.”

No confirmation; no denial.

The survival of wild tigers depends on the world responding to what Chinese officials are not saying. Otherwise, the conversation stops cold, which only benefits those invested in farming tigers to build a voracious market for luxury goods like tiger-skin rugs and tiger-bone wine.

Here are some of the key points spoken and unspoken by China’s Foreign Ministry:

China is committed to “tackle illegal activities,” Hua Chunying said. What Hua avoided mentioning was the fact that the State Forestry Administration has already begun allowing some trade in tiger skins from farms and has helped pay for farm wineries mass-producing tiger-bone wine. Hua also avoided the fact that the State Forestry Administration has openly advocated fully reopening legal tiger trade in China—the very trade blamed for causing wild tiger populations to plummet before China banned tiger-bone trade in 1993. Never mind that all of the above is happening while the 1993 remains in place.

At this week’s press conference, Hong Lei handily chose not to answer the question asked. He did, however, mention China’s laws “protecting wild tigers.” China’s Wildlife Protection Law actually mandates the “domestication” and “consumption” of tigers and other endangered species, which a growing alliance of Chinese inside China are lobbying to change.

“Poaching, trading of tiger bones and using them as medicine are fully banned,” Hong said. But what about the use of the tiger skeletons now steeping in vats of wine at China’s farms, which now hold some 6,000 tigers? Why is that allowed? No one asked. And had they done so, there likely would have been no confirmation or denial.

Shouldn’t the world insist on straight answers when the last wild tigers are at stake?

Posted by J. A. Mills on January 22nd, 2015 in India, News, Tigers

A few years ago, I suggested to a coalition of conservation groups that we use crowdsourcing to engage the world in saving wild tigers and to come up with some fresh, out-of-our-box ideas because business-as-usual was not working.

Two prominent wildlife organizations nixed the idea. “That is not our brand,” one of their people said. “Our brand is that we are the ones who have the solutions.” Never mind that millions of dollars had been spent over decades of effort and wild tigers were still in dangerous decline.

© Brian Gratwicke

This week, headlines joyfully called out India’s announcement that wild tiger numbers there may be up by as much as 30 percent. That is good news indeed, if the numbers are right. But here is the risk: Many people may take this to mean wild tigers are out of danger, and some organizations married to that we’ve-got-it-covered brand will be playing down the potentially fatal list of caveats.

It would be better for wild tigers if the world took India’s new census as proof there is hope for their comeback and long-term survival while keeping in mind the less encouraging numbers at hand. Even if wild tiger numbers are up by some 300 animals in India, they are down in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. In all, there still may be only 3,000 or so wild tigers left in the world. Meanwhile, there are as many as 6,000 tigers on farms in China, where tiger skeletons are steeping in vats of wine as farm backers anticipate a full lifting of China’s ban on tiger-bone trade. These entrepreneurs hope to stimulate demand for their products among China’s 1.4 billion people first, then the world.

The problem with this scenario is that wine made with the bones of wild tigers is considered superior, more prestigious and exponentially more valuable. If only the tiniest fraction of China’s would-be tiger-bone consumers were to seek the “best,” organized criminal networks are in place to provide – and entire wild tiger populations could be lost before we know they’re gone, as happened in India’s Sariska Tiger Reserve in 2005 and again in its Panna National Park in 2009.

In 1992, the United States threatened trade sanctions against China because its use of tiger bone in medicine was threatening the survival of wild tigers throughout their Asian range. China banned all use of tiger bone in 1993. There were an estimated 5,000 to 7,000 tigers in the wild back then, and hundreds of thousands fewer Chinese with a lot less expendable income. Rekindling an appetite for tiger-bone wine in China today would pose a far greater threat to many fewer tigers in the wild.

Tiger farming is the “elephant in the room,” casting a dark shadow over any progress for wild tigers. Let us celebrate India’s good news by insisting that the “elephant” be taken into account.

Posted by J. A. Mills on January 12th, 2015 in China, Tigers, U.S.

On November 12, 2014, China and the United States—the world’s No. 1 and No. 2 carbon emitters, respectively—announced a bilateral promise to take significant climate action. The world applauded because its climatic fate rests, in significant part, with the two superpowers ending their I-won’t-unless-you-do stalemate.

© Eric Ash

The fate of the world’s last wild tigers is caught up in a similar China-U.S. tit-for-tat, and similar bilateral action is necessary to ensure their survival. If China and the U.S. can make the enormous economic and legal changes necessary to rein in global warming, surely they can rein in the relative handful of entrepreneurs and investors who own the approximately 6,000 captive tigers in private hands in each country—which, combined, number four times those struggling to survive in the wild.

In 2007, the U.N. treaty on international trade in endangered species—to which nearly every country on Earth is a member—decided that tigers should not be raised like livestock for commercial exploitation. In China, with the blessing of the country’s wildlife protection law, tigers are farmed for consumption of their parts and products. Some important observers in the international community argue that the thousands of U.S. tigers used for paid cub-petting and in private zoos are not so different.

Just as certain Chinese officials refused to cut carbon emissions unless the U.S. did so in equal measure, so are certain other Chinese officials refusing to phase out tiger farming without in-kind U.S. action. And who can blame them? At least Chinese officials know where China’s captive tigers are located. No U.S. agency, at the national or state level, knows how many tigers live here, where they all live, who owns them, how they’re all kept and—most worrying—what happens to them when they die. Do their skins and bones go into trade as the skins and bones of China’s farmed tigers do? Does anyone really believe some parts of U.S. tigers don’t go into trade when potential profits rival those from selling illegal drugs and guns?

The list of ways captive tigers in China and the U.S. differ is long—perhaps as long as the list of how China and the U.S. differ in their contributions to climate change. But the fundamental truth in both cases is that China and the U.S. must take unprecedented bilateral action to prevent irreversible disasters—one involving Earth’s atmosphere, the other the globally-loved king of Asia’s jungle.

If the U.S. and China can set aside their tit-for-tat impasse to forge a deal on climate change, surely they can do the same to stop the exploitation of captive tigers that keeps alive the demand that drives the killing of wild tigers.

Sounds promising for tigers, rhinos, bears, and other endangered wild animals now commercially farmed in China. But here’s the rub, as spelled out by Xinhua: “The decision also stipulates that the use of wild animals for non-edible purposes, including scientific research, medical use and display, shall be subject to strict examination, approval and quarantine inspection procedures in accordance with relevant regulations.” Tigers are farmed for their bones, rhinos for their horns, and bears for the bile in their gall bladders, all for use in traditional Chinese medicine. So, while wet markets in China may be closing, factory farms for endangered species appear to be carrying on as usual, despite the inherent disease risk.

Sounds promising for tigers, rhinos, bears, and other endangered wild animals now commercially farmed in China. But here’s the rub, as spelled out by Xinhua: “The decision also stipulates that the use of wild animals for non-edible purposes, including scientific research, medical use and display, shall be subject to strict examination, approval and quarantine inspection procedures in accordance with relevant regulations.” Tigers are farmed for their bones, rhinos for their horns, and bears for the bile in their gall bladders, all for use in traditional Chinese medicine. So, while wet markets in China may be closing, factory farms for endangered species appear to be carrying on as usual, despite the inherent disease risk.

So now China has, on the one hand, 6,000 tigers in SFA-supported battery farms with wineries brewing a fortune in tiger-bone wines. It also is trying to buy up South Africa’s rhino horn stocks, while simultaneously starting to farm more with

So now China has, on the one hand, 6,000 tigers in SFA-supported battery farms with wineries brewing a fortune in tiger-bone wines. It also is trying to buy up South Africa’s rhino horn stocks, while simultaneously starting to farm more with  This graphic from Blood of the Tiger offers a quick overview of wild tiger numbers over that past 20 years. As the number of tigers in China’s farms went up, those in the wild went down. The correlation: demand increased for wild tiger parts and products as the burgeoning farms tacitly promised a reopening of tiger trade between the lines—which is where most mainland Chinese ascertain news from their government.

This graphic from Blood of the Tiger offers a quick overview of wild tiger numbers over that past 20 years. As the number of tigers in China’s farms went up, those in the wild went down. The correlation: demand increased for wild tiger parts and products as the burgeoning farms tacitly promised a reopening of tiger trade between the lines—which is where most mainland Chinese ascertain news from their government. The New York Times recently wrote a

The New York Times recently wrote a